Andreas Werckmeister (1645–1706) was a musician and expert on the organ. Compared to Kirnberger, his life seems outwardly dull. He got his musical training from his uncles, and from the age of 19 to his death he worked as an organist in three German towns. That’s about all I know.

His fame comes from the tremendous impact of his his theoretical writings. Most importantly, in his 1687 book Musikalische Temperatur he described the first ‘well tempered’ tuning systems for keyboards, where every key sounds acceptable but each has its own personality. Johann Sebastian Bach read and was influenced by Werckmeister’s work. The first book of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier came out in 1722—the first collection of keyboard pieces in all 24 keys.

But Bach was also influenced by Werckmeister’s writings on counterpoint. Werckmeister believed that well-written counterpoint reflected the orderly movements of the planets—especially invertible counterpoint, where as the music goes on, a melody that starts in the high voice switches to the low voice and vice versa. Bach’s Invention No. 13 in A minor is full of invertible counterpoint:

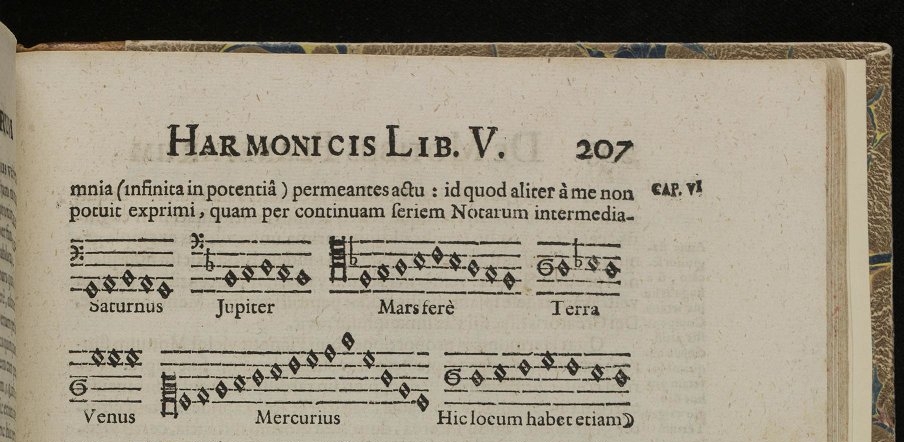

The connection to planets may sound bizarre now, but the ‘music of the spheres’ or ‘musica universalis’ was a long-lived and influential idea. Werckmeister was influenced by Kepler’s 1619 Harmonices Mundi, which has pictures like this:

But the connection between music and astronomy goes back much further: at least to Claudius Ptolemy, and probably even earlier. Ptolemy is most famous for his Almagest, which quite accurately described planetary motions using a geocentric system with epicycles. But his Harmonikon, written around 150 AD, is the first place where just intonation is clearly described, along with a number of related tuning systems. And it’s important to note that this book is not just about ‘harmony theory’. It’s about a subject he calls ‘harmonics’: the general study of vibrating or oscillating systems, including the planets. Thinking hard about this, it become clearer and clearer why the classical ‘quadrivium’ grouped together arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy.

In Grove Music Online, George Buelow digs a bit deeper:

Werckmeister was essentially unaffected by the innovations of Italian Baroque music. His musical surroundings were nourished by traditions whose roots lay in medieval thought. The study of music was thus for him a speculative science related to theology and mathematics. In his treatises he subjected every aspect of music to two criteria: how it contributed to an expression of the spirit of God, and, as a corollary, how that expression was the result of an order of mathematical principles emanating from God.

“Music is a great gift and miracle from God, an art above all arts because it is prescribed by God himself for his service.” (Hypomnemata musica, 1697.)

“Music is a mathematical science, which shows us through number the correct differences and ratios of sounds from which we can compose a suitable and natural harmony.” (Musicae mathematicae Hodegus curiosus, 1686.)

Musical harmony, he believed, actually reflected the harmony of Creation, and, inspired by the writings of Johannes Kepler, he thought that the heavenly constellations emitted their own musical harmonies, created by God to influence humankind. He took up a middle-of-the-road position in the ancient argument as to whether Ratio (reason) or Sensus (the senses) should rule music and preferred to believe in a rational interplay of the two forces, but in many of his views he remained a mystic and decidedly medieval. No other writer of the period regarded music so unequivocally as the end result of God’s work, and his invaluable interpretations of the symbolic reality of God in number as expressed by musical notes supports the conclusions of scholars who have found number symbolism as theological abstractions in the music of Bach. For example, he not only saw the triad as a musical symbol and actual presence of the Trinity but described the three tones of the triad as symbolizing 1 = the Lord, 2 = Christ and 3 = the Holy Ghost.

The Trinity symbolism may seem wacky, but many people believe it pervades the works of Bach. I’m not convinced yet—it’s not hard to find the number 3 in music, after all. But if Bach read and was influenced by the works of Werckmeister, maybe there really is something to these theories.

Werckmeister’s tuning systems

As his name suggests, Werckmeister was a real workaholic. There are no less than five numbered tuning systems named after him—although the first two were not new. Of these systems, the star is Werckmeister III. I’ll talk more about that one next time. But let’s look briefly at all five.

Werckmeister I

This is another name for just intonation. Just intonation goes back at least to Ptolemy, and it had its heyday of popularity from about 1300 to 1550. I discussed it extensively starting here.

Werckmeister II

This is another name for quarter-comma meantone. Quarter-comma meantone was extremely popular from about 1550 until around 1690, when well temperaments started taking over. I discussed it extensively starting here, but remember:

All but one of the fifths are 1/4 comma flat, making the thirds built from those fifths ‘just’, with frequency ratios of exactly 5/4: these are the black arrows labelled 0. Unfortunately, the sum of the numbers on the circle of fifths needs to be -1. This forces the remaining fifth to be 7/4 commas sharp: it’s a painfully out-of-tune ‘wolf fifth’. And the thirds that cross this fifth are forced to be even worse: 8/4 commas sharp. Those are the problems that Werckmeister sought to solve with his next tuning system!

Werckmeister III

This was probably the world’s first well tempered tuning system! It’s definitely one of the most popular. Here it is:

4 of the fifths are 1/4 comma flat, so the total of the numbers around the circle is -1, as required by the laws of math, without needing any positive numbers. This means we don’t need any fifths to be sharp. That’s nice. But the subtlety of the system is the location of the flatted fifths: starting from C in the circle of fifths they are the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and… not the 4th, but the 6th!

I’ll talk about this more next time. For now, here’s a more elementary point. Comparing this system to quarter-comma meantone, you can see that it’s greatly smoothed down: instead of really great thirds in black and really terrible ones in garish fluorescent green, Werckmeister III has a gentle gradient of mellow hues. That’s ‘well temperament’ in a nutshell.

For more, see:

• Wikipedia, Werckmeister temperament III.

Werckmeister IV

This system is based not on 1/4 commas but on 1/3 commas!

As we go around the circle of fifths starting from B♭, every other fifth is 1/3 comma flat… for a while. But if we kept doing this around the whole circle, we’d get a total of -4. The total has to be -1. So we eventually need to compensate, and Werckmeister IV does so by making two fifths 1/3 comma sharp.

I will say more about Werckmeister IV in a post devoted to systems that use 1/3 and 1/6 commas. But you can already see that its color gradient is sharper than Werckmeister III. Probably as a consequence, it was never very popular.

For more, see:

• Wikipedia, Werckmeister temperament IV.

Werckmeister V

This is another system based on 1/4 commas:

Compared to Werckmeister III this has an extra fifth that’s a quarter comma flat—and thus, to compensate, a fifth that’s a quarter comma sharp. The location of the flat fifths seems a bit more random, but that’s probably just my ignorance.

For more, see:

• Wikipedia, Werckmeister temperament V.

Werckmeister VI

This system is based on a completely different principle. It also has another really cool-sounding name—the ‘septenarius tuning’—because it’s based on dividing a string into 196 = 7 × 7 × 4 equal parts. The resulting scale has only rational numbers as frequency ratios, unlike all the other well temperaments I’m discussing. Werckmeister described this system as “an additional temperament which has nothing at all to do with the divisions of the comma, nevertheless in practice so correct that one can be really satisfied with it”. For details, go here:

• Wikipedia, Werckmeister temperament VI.

Werckmeister on equal temperament

Werckmeister was way ahead of his time. He was not only the first, or one of the first, to systematically pursue well temperaments. He also was one of the first to embrace equal temperament! This system took over around 1790, and rules to this day. But Werckmeister advocated it much earlier—most notably in his final book, published in 1707, one year after his death.

There is an excellent article about this:

• Dietrich Bartel, Andreas Werckmeister’s final tuning: the path to equal temperament, Early Music 43 (2015), 503–512.

You can read it for free if you register for JSTOR. It’s so nice that I’ll quote the beginning:

Any discussion regarding Baroque keyboard tunings normally includes the assumption that Baroque musicians employed a variety of unequal temperaments, allowing them to play in all keys but with individual keys exhibiting unique characteristics, the more frequently used diatonic keys featuring purer 3rds than the less common chromatic ones. Figuring prominently in this discussion are Andreas Werckmeister’s various suggestions for tempered tuning, which he introduces in his Musicalische Temperatur. This is not Werckmeister’s last word on the subject. In fact, the Musicalische Temperatur is an early publication, and the following decade would see numerous further publications by him, a number of which speak on the subject of temperament.

Of particular interest in this regard are Hypomnemata Musica (in particular chapter 11), Die Nothwendigsten Anmerckungen (specifically the appendix in the undated second edition}, Erweiterte und verbesserte Orgel-Probe (in particular chapter 32), Harmonologia Musica (in particular paragraph 27) and Musicalische Paradoxal-Discourse (in particular chapters 13 and 23-5). Throughout these publications, Werckmeister increasingly championed equal temperament. Indeed, in his Paradoxal Discourse much of the discussion concerning other theoretical issues rests on the assumption of equal temperament. Also apparent is his increasing concern with theological speculation, resulting in a theological justification taking precedence over a musical one in his argument for equal temperament. This article traces Werckmeister’s path to equal temperament by examining his references to it in his publications and identifying the supporting arguments for his insistence on equal temperament.

In his Paradoxal Discourse, Werckmeister wrote:

Some may no doubt be astonished that I now wish to institute a temperament in which all 5ths are tempered by 1/12, major 3rds by 2/3 and minor 3rds by 3/4 of a comma, resulting in all consonances possessing equal temperament, a tuning which I did not explicitly introduce in my Monochord.

This is indeed equal temperament:

And in a pun on ‘wolf fifth’, he makes an excuse for not talking about equal temperament earlier:

Had I straightaway assigned the 3rds of the diatonic genus, that tempering which would be demanded by a subdivision of the comma into twelve parts, I would have been completely torn apart by the wolves of ignorance. Therefore it is difficult to eradicate an error straightaway and at once.

However, it seems more likely to me that his position evolved over the years.

What’s next?

You are probably getting overwhelmed by the diversity of tuning systems. Me too! To deal with this, I need to compare similar systems. So, next time I will compare systems that are based on making a bunch of fifths a quarter comma flat. The time after that, I’ll compare systems that are based on making a bunch of fifths a third or a sixth of a comma flat.

For more on Pythagorean tuning, read this series:

For more on just intonation, read this series:

For more on quarter-comma meantone tuning, read this series:

For more on well-tempered scales, read this series:

• Part 1. An introduction to well temperaments.

• Part 2. How small intervals in music arise naturally from products of integral powers of primes that are close to 1. The Pythagorean comma, the syntonic comma and the lesser diesis.

• Part 3. Kirnberger’s rational equal temperament. The schisma, the grad and the atom of Kirnberger.

• Part 4. The music theorist Kirnberger: his life, his personality, and a brief introduction to his three well temperaments.

• Part 5. Kirnberger’s three well temperaments: Kirnberger I, Kirnberger II and Kirnberger III.

For more on equal temperament, read this series:

I had no idea the history of tuning systems was so rich. This is all fascinating!

Given the plethora of well temperaments that evidently existed in Bach’s day, I wonder if anyone has ever speculated that Bach didn’t have any single tuning system in mind when he wrote The Well-Tempered Clavier, but all of the different well temperaments he knew of. Is it possible that the work wasn’t meant to showcase the advantages of one specific version of well temperament (as is often suggested), but was instead intended to be a device for musicians to compare the overall character of one tuning system to another?

The history of tuning systems is very rich, especially when it comes to the era of well temperaments. There was an explosion of diversity before equal temperament took over. So I’m trying to bring some order to it, or at least reveal some patterns in the most popular systems. But meanwhile I’m only just now learning them.

That’s definitely possible, but so far all the papers I’ve looked at seem to argue Bach favored one particular temperament or another. Taken en masse they become extremely unconvincing, sort of like “I am Spartacus”. For example, here’s one that claims that something called Lehman’s temperament is favored mathematically:

• Emmanuel Amiot, Discrete Fourier transform and Bach’s good temperament.

However, they admit that their measure of quality is maximized by equal temperament, which was, they claim, “abhorrent to Bach”. So I’m very suspicious. (I don’t even know any solid evidence that equal temperament was abhorrent to Bach!)

I’ll keep an eye out for your theory, which would be a refreshing change of pace.

Thank you very much for this great illustration. For some time I have been trying to calculate the frequencies for Pythagoras, Kirnberger III and Werckmeister III with a given concert pitch and tuning note, but only with this description did I get it right, in the sense that the results match the data of a professional piano synth to one decimal place. But now I’m frustrated. I fail when calculating the frequencies for Sixth-Comma Meantone. If I start, in a similar way to the other tunings, with the concert pitch at 440Hz, with the circle of fifths rotated according to the tuning note (in this case D), only for Sixth-Comma Meantone I then reduce the fifths by -1/6 of a Syntonic-Comma, then I still get the same results as the professional synth for 10 out of 12 notes, but only if I shift the +5/6 by a fifth, unlike the illustration of Carey Beebe. And then there are also two notes (https://github.com/ank19/renoise-interval/blob/495d971f204c4a4a67eaa06bc183dc90b72e47a8/org.bridgi.interval.xrnx/test.lua#L270-L282) whose frequency is not significantly different, but still significantly different compared to the other tunings, where the numbers match to one decimal place compared to the pro synth. Do you have any hint where my lapse in thought is?

I’m glad this blog article was helpful! Any slight discrepancies left between your calculations of Pythagorean, Kirnberger III and Werckmeister III and those of a ‘professional’ could easily be due to choices regarding whether to use the Pythagorean or syntonic comma — and where to put the resulting schisma. I explained what seems to be the ‘standard’ choice for Pythagorean and Kirnberger III, but not for Werckmeister III.

I am busy doing my taxes today, so I don’t have the stomach for further calculations right now. However, I will be posting an article about sixth-comma meantone! So if you can wait, let’s talk about this then, when my mind is on that subject.

Thanks, John – I’ll be patient and looking forward to your post.